|

When I first met the Babetta, alias the Jawa type 207/300 moped, it was a case of love at first sight. Not that I had not seen plenty of 50cc mopeds before, but this one, I felt, was something different. It was simply not "it" but "she" - a distinctive personality in her own right, and very feminine at that, in the best sense of the word. Nor was I the only one to think so. Stefan Micek, editor of "Zivot" a Czech Magazine, who accompanied me on this visit to the Povazske Strojarne plant which produces them was equally enraptured. Nothing you could put your finger on - just a 49cc single-cylinder that renders 1.1 kW, enough to cart a load of 85kg around at up to 40 kph [25mph] on those slender 2.25 x 16" tyres. Yet there was something so provoking about her looks that Stefan and I immediately started hatching plans about where to take a couple of these beauties. And as each of us already had two trips to Africa in his logbook, and every intention of going there again, we promptly decided to take a pair of Babettes on our joint visit to Africa

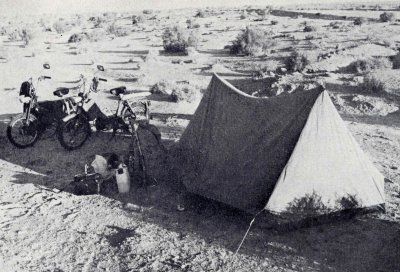

The journey was to consist of three distinct parts. First we would ride the Babetta across West Germany and France to Marseilles, which in mid winter would be more than most people would care to attempt – and would also test the two ladies to the limit, so as to bring out any possible flaws in them. Then once across the Mediterranean, we would take our companions round what travellers call the "Grand Circuit" of the Sahara, exposing them to the scorching heat, the sand that penetrates every known filter and seal, and to those great and abrupt differences between day and night temperatures that make the Sahara such a proverbial testing ground of men and machines alike. As by the end of that circuit we expected to be rather saddle-sore, we planned to transfer to four or more wheels for a tour of southern Algeria, Mali, Senegal, the Niger and the Upper Volta, taking a bus where we could, or a lift on a lorry where there were no bus lines, before returning to Algeria and the waiting Babettes. Africa is vast and varied; much of the territory covered on this trip would be new to us; and travelling by moped would we felt, add some novelty and excitement even to those parts of which we had crossed before by more conventional means.

Even for all the meticulous advanced planning, neither of us felt too sure of himself as we cleared the Czech customs at Pomezi and headed out for Bayreuth. We knew that what we had set out to accomplish would be asking quite a lot of a couple of dainty and fragile-looking ladies; and for all our faith in the men who had designed and built them, we were half prepared to see the Babettes fold up on us before we were half-way through.

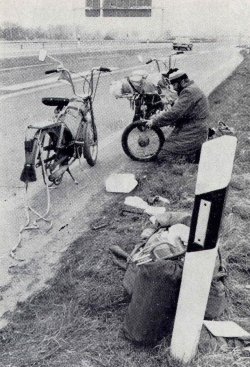

Germany is notoriously a country where the law is not to be taken lightly, and where the traffic police are sticklers, used to enforcing every last comma of the highway code. Being a good deal slower than the minimum speed allowed on the German autobahn system, we had done some preliminary map work and decided on highway No.27, a second-class road leading through the ancient and picturesque town of Wurzburg. Only some distance beyond the town did we come to realise that although we were on the correct road we were heading in the wrong direction. That added some 80 kilometres to our route, and made the first dent in our fairly tight time schedule. The second followed shortly afterwards, in the form of a puncture in Stefan's rear tyre. After a short time of hectic work and frantic cursing in the rain, we set off again, at our stately 32 to 35 kph [20 - 22 mph], towards Frankfurt. That name may mean sausages, trade fairs, or the Eintract football club to you; to us, in meant some well-deserved and urgently needed rest before we continued on into the driving rain.

We pitched our tent for the night some 140 km [88 miles] short of the French border, noting miserably that the tent, our sleeping bags and most of our belongings were dripping wet. As you can imagine we spent some uneasy and uncomfortable hours pretending to sleep. The next night, near Saarbrucken, we were wiser, and set up the tent on some plastic sheeting, using more of the same stuff to wrap up as much as we could of our gear. After a night of real rest, we entered France relatively dry and in high spirits. On the outskirts of Paris, we stopped for another close look at the map, fearful of spending the rest of the day looking for the Czech embassy where we were heading. We need not have bothered: The Avenue Charles Fleguet is almost in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, the best landmark we could have hoped or wished for.

After three days of sightseeing in Paris, we felt sufficiently dry and recuperated to start out on those 900 km [560 miles] to Marseilles, where, as the travel agency assured us, the M/V Russion was due to leave for Algeria on March 11th. That left us 4½ days, a leisurely spin down to the coast, with plenty of sight-seeing stops on the way - or so we thought. In fact, however, most of the margin of time we had in hand was gradually dissipated by a succession of minor hold-ups: a spark plug that packed up here, a wrong turning on a badly marked road there, and scores of policemen who stopped us to remonstrate about the fact that we were not wearing crash-helmets. None of them fined us - when we explained that helmets were not mandatory for moped riders in our country, the police invariably condescended to turn a blind eye to our misdemeanour; but the series of enforced five - or ten-minute halts cost us so much time that we reached the harbour of Marseilles only at half past two in the morning.

Even so, we had not done too badly. We had covered 2200 km [1375 miles] without any major mishap, and could now spend the rest of the night, and get a little sleep, right underneath that ancient lighthouse which was soon to be the last bit of Europe we would see for some time. In the morning, we cleaned and checked our machines, rode down to the quay - and promptly found no trace of the Russion. Dismay, confusion, hurried inquiries, and finally it transpired that our boat had been replaced at the last minute by the 'Hogger', the ship in fact that two years previously had carried us from Oran to Alicante. But that was not the end of the fracas. There is some sort of ruling that forbids travellers to venture into Algeria on a moped: and although like most rulings in that part of the world it can be circumnavigated, the procedure took some time and effort, and left our nerves in no state for the further trial that awaited them. In view of that ruling, apparently, the steamship company has no tariff for the carriage of mopeds, or of motorcycles with a displacement of less than 100cc. No tariff, no tickets; and no tickets, no carriage; that was the simple logic of the cashiers who doggedly refused to let our machines be lifted on board.

After exhausting all our powers of persuasion in vain, we hit on the obvious solution: our Babettes suddenly grew into full-blown motorcycles of 100cc swept volume, and were taken aboard as such without any further ado. Wonderful how a simple though obviously false declaration can cut across miles of red tape.

We had hoped to spend three days looking around the city of Algiers, but in the end we saw remarkably little of it in that time. There were the visas to the Republic of Niger to obtain; five-litre fuel canisters to fit to our grossly overloaded mopeds; and tin of engine oil to pack in case the petrol pumps en route did not stock any two-stroke mixture; a burst fuel hose to replace; and of course, we had to check the Babettes down to the last nut and bolt before venturing out into the Sahara. At least we could lessen the burden on our machines by leaving our caps, sweaters and winter footwear in safe custody in Algiers, as we were not likely to need them before returning to Europe. And then with everything shipshape, we confidently headed out for the foothills of the atlas mountains.

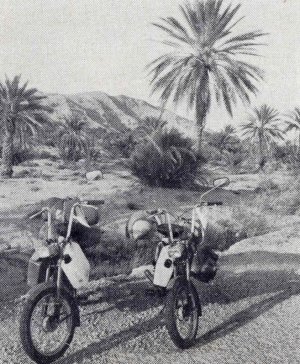

The ancient Greeks credited the Atlas range with supporting the firmament; and climbing up that tortuous road, the mountain passes a thousand metres above sea level, made us feel they had not been far from the truth. What with stomach cramps and the sturdy little engines labouring heavily underneath us, we had to make frequent stops; at least we could admire and photograph the superb scenery to our hearts' content. Finally, at 4 pm. and with the engines literally sizzling, we reached the summit, throttle down, and on the long descent whirled up the first swirling cloudlets of genuine Sahara sand.

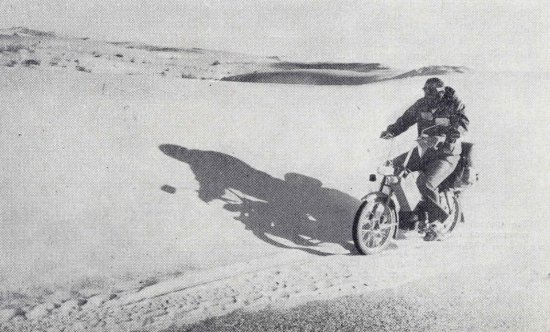

Heaven knows why people tend to think of the Sahara as just a vast monotonous expanse. It is in fact enormously varied, though very rarely pleasant. Long stretches of it are all stones, the sort of place where a fall would spell disaster. Then, suddenly, you find yourself engulfed in deep drifts of fine, dusty sand. All very well for the occasional lorry driver, who on getting stuck just backs out and then roars through the drifts at full throttle, literally ploughing his way through by sheer force of all those 'horses' under his bonnet. But for us, it meant walking, for miles on end, and pushing the heavily laden mopeds along by what force was left in our aching muscles.

All exhilaration had left us by the time we reached Biskra, a tiny township whose crooked little alleys abound with market stalls, coffee houses serving green tea as well as coffee, and shops selling what few wares are available in these parts. It took us three days at the home of a friendly local, whose address we had received in Algiers, before we felt ready to push on to Ouargia, a large modern town some 400km [250 miles] away. About half way along this route, we stopped for a rest at the ancient town of Toggourt, once the capital of a mighty empire. All that is left of its former glory is a splendid mosque. We made the mistake of giving a local guide a dinar to explain the history of this place to us, and then had to flee while he was only just warming up on the subject; he is probably still talking away. Anyway, he detained us long enough for us to reach Ouargia well after dark, but fortunately some Czech architects we had met on the boat had briefed us about the local geography so thoroughly that we had no navigational problems even in pitch darkness.

The two days in Ouargia revived our parched bodies and sagging spirits, and then faced us with a problem. This was the end of the road for our Babettes - what lay beyond was, we had decided, was no longer fit for 'female' company. We could either continue straight ahead to Tamanrasset, or else leave Algeria via Reggan, pass through the old French fort of Bidon, and make for Tessalit in Mali, to re-approach the fringes of civilisation at Gao. As we had both been to Tamanrasset before, we finally and rather hesitantly chose this latter route, 1500km [ 940 miles] long and not exactly hospitable.

With the mopeds safe in the custody of some Czechs resident in Ouargia, we were down to hitch-hiking on the heavy trucks, mostly Berliets, which ply the desert roads between Algiers and Gao. This is not the most reliable mode of travelling, as those trucks run as and when the Algerian date crop ripens. Fortunately, the harvest season begins in March, and this was a bumper year for dates, so we could actually pick and choose our lorries, After a rather unsatisfactory lift to Adrar, we were picked up by a rotund and genial man called Hassan. He seated us in what at the time appeared to be dignity and comfort on top of his cargo of dates, firewood and water, with a supply of dried goat's meat close at hand. Both the dignity and comfort ceased when, before our incredulous gaze, the thermometer rose to a murderous 62 deg C, or 143.6 deg F. How we survived those five days and 1000km [625 miles] on top of Hassan's Berliet is more than either of us can comprehend, but we reached Tassalit in Mali still more or less alive. The local customs official looked hot and disinterested, until he saw our Czech passports. Then his face lit up - he had been to school in Czechoslovakia fifteen years ago, he was delighted beyond words to see us, and he promptly took us to what he claimed to be the best mineral water the Sahara has to offer - naturally, right there in Tessalit. Anyway, the water was really good, and indulging in the luxury of a bath and a shave after all that time made us almost forget all our tribulations. We set out on the final 500km to Gao quite eagerly, accepting the dates, the Berliet and the heat as just part of the routine.

By this time we were definitely leaving the Sahara. The sand gradually gave way to, at first sparse and intermittent, then even denser and more frequent patches of grassland, with herds of antelopes fleeing rather reluctantly before the rumble of our engine. After two days on the date-bedded grill, some slender minarets and cupolas emerged on the horizon. We had made it to Gao, and to three days of badly needed rest.

Since hitch-hiking in these parts had turned out much less of a problem than we had anticipated, we decided to use the same mode of transport for a circular tour to Niamey in Niger, then to Ouagadogou in the Upper Volta, and back to Gao for another two-day rest. Rest is really not the most appropriate word for two days of hectic inquiring before we found a truck driver prepared to take us back to Reggan. This benefactor took not only us, but also one Canadian, one Dutch girl, and two Algerians; moreover, he' proposed to take on board seventy sheep which he said he was going to purchase on the way. Only later did it dawn on us that those evil-smelling beasts which transformed our journey into pure torture were bought out of the fares the six of us had paid. Even though ten of the sheep failed to withstand the trip, the driver evidently made a handsome profit on the transaction. We, the two-legged passengers, were too far gone to have any sympathy left to expend on the wretched animals.

Reggan is linked by regular bus routes to most of the major Algerian towns; so returning to Ouargia and our Babettes was entirely unromantic and, except for the heat, about the least strenuous part of our whole journey. Once back in the saddl es, we made a bee-line for the port of Algiers, so as not to miss the last boat which would take us back to Europe in time for us to get home before our leave expired. es, we made a bee-line for the port of Algiers, so as not to miss the last boat which would take us back to Europe in time for us to get home before our leave expired.

Although not all of the trip had been by the Babettes [ that would have been suicidal ], the two little bikes had carried us many thousands of kilometres, and had proven just how good these little bikes are.

|